Designs in Particle Poetics

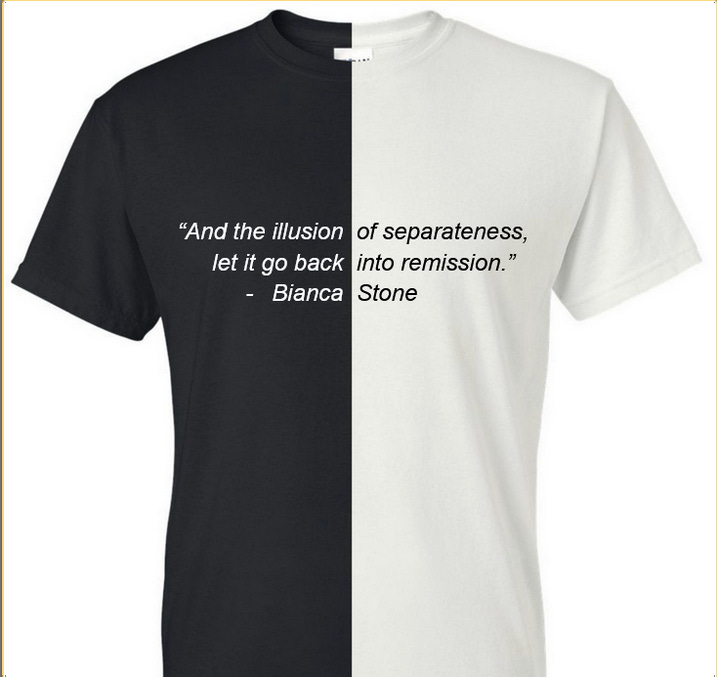

a student's t-shirt might help you understand my obsession with particle poetics

This summer, when I was not sliding down scorching sand hills with my amazing five-year-old, I spent a lot of time chewing on a course I designed and taught this past spring, ENGL310: Particle Poetics. Between January and May, when a lot of really shitty things were happening in the physical and imaginary worlds, a lot of really cool things were also happening in the physical and imaginary worlds I experienced. I’d like to tell you about four of those cool things today, ending with a student design.

Four Really Cool Things

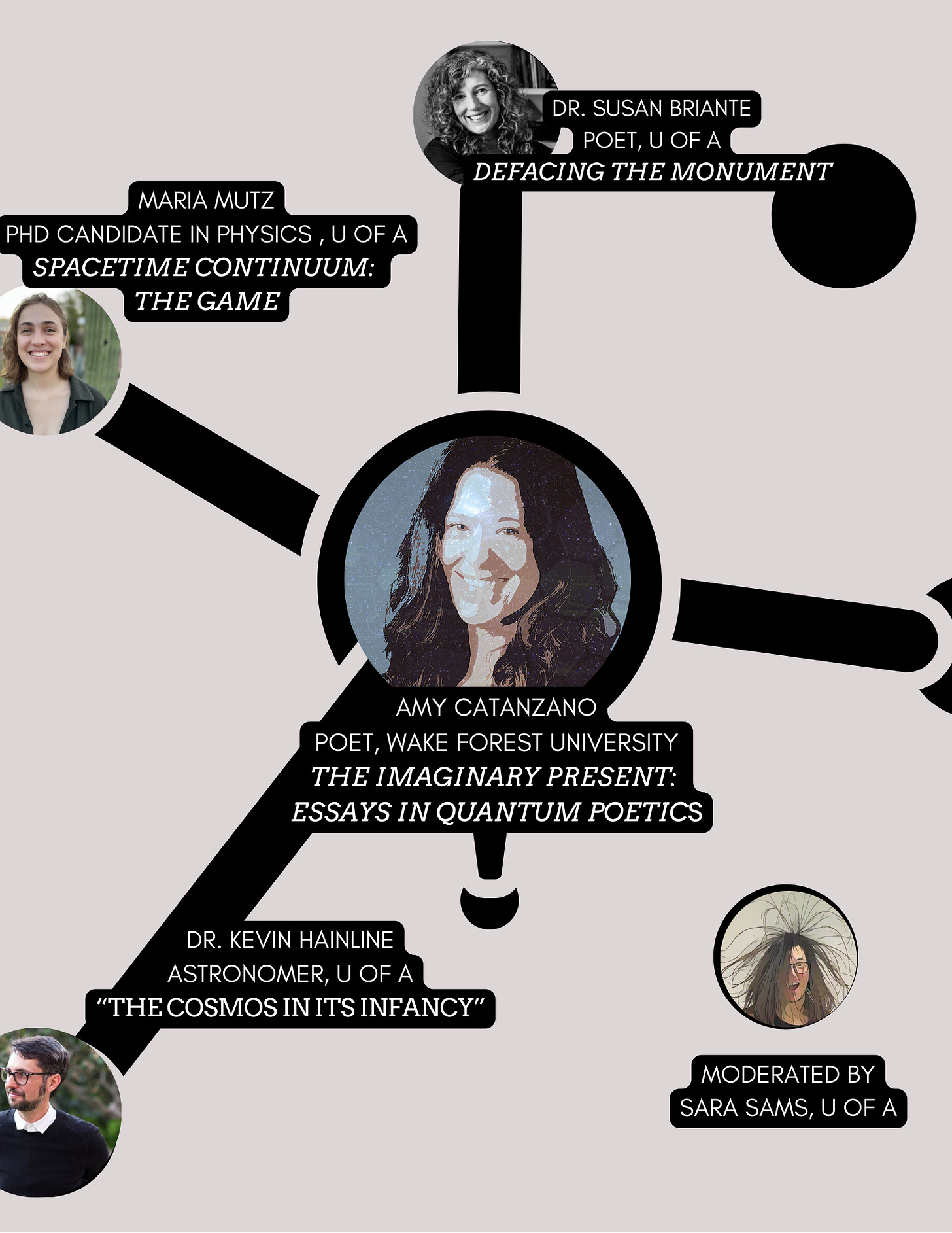

First, I was able to invite the poet & scholar Dr. Amy Catanzano out to Tucson, and she participated in a reading and panel discussion that I believe will go on infinitely feeding my store of food for thought. Her recently published The Imaginary Present: Essays in Quantum Poetics should, I think, be assigned to every student of philosophy, physics, and (of course )poetry, from now until forever, with the small caveat that “Time is Not an Arrow” — as Catanzano explains in her introduction of that name:

“Because of its special relationship to language and thinking, poetry is poised to respond to a question that science on its own has been unable to answer. That question is, What does quantum physics mean? Quantum poetics takes this question on by harnessing poetry as an artistic form of language that can both enact and interpret physics. In physics and poetry, time is not an arrow following a trajectory through a human past, present, and future. In physics and poetry, time is spacetime, combining the dimension of time with the three dimensions of space in one manifold known as the fourth dimension. In relativity, spacetime warps the spacetime in its vicinity, which, in turn, warps it. When poets are alert to how spacetime behaves, they can work with the spacetime on the page, or in any other medium, with greater critical and artistic intention. Similarly, when scientists are alert to how poets and artists experiment with spacetime, they can pursue science with broader perspectives.”

Second, to help us better understand Catanzano’s work and to more thoughtfully read other poets whose imaginations and minds have been influenced by discoveries in physics, I got some help from UA’s Dr. Charles Wolgemuth. A bio-physicist who studies the way cells “produce the force necessary to create and maintain their shape, grow, and move” (which is much more complicated than I had imagined), Dr. Wolgemuth seemed genuinely excited to explain some of the “basics” of relativity to my students and to myself. He was able to do this patiently, and in a way that things actually began to click for us.

And then, he volunteered to come back to talk about how the processes and cultural values of science are (as he sees them) related to existentialist thought. I hope to share some more insights from those lectures at a later date. But for now, let me tell you about how those lectures led me to a third Very Cool Thing. When Dr. Wolgemuth asked us who we thought of when we thought of existentialism, I did have, like, a fleeting image of this kind of dude:

But then, our guest lecturer paused, letting us think. My mind went racing back to Simone de Beauvoir, who I read in deep glugs while seeking my own undergraduate degree in creative writing, back in 2008.

I had honestly forgotten The Second Sex was in me, somewhere, and I am glad I re-discovered this by reading Skye C. Cleary. Man, third cool thing! Can you dream up a better name for a philosopher?* On page XXV of How to be Authentic: Simone de Beauvoir and the Quest for Fulfillment, Cleary writes that her book is about “tensions”— particularly between 1) how we create ourselves and 2) how that creation process is always one of inter-connectivity. On the left, in corner #1, we might see a unique self engaging in a Sisyphean attempt to transcend the various facticities** of life and push the individual boulder up the hill; on the right, in corner #2, there is an entire community yelling at you that the struggle up that hill is not an individual struggle at all.

If other people “influence how we create ourselves” and we, in turn, “influence how other people create themselves,” then the philosophy must take that inter-connectivity into consideration in order to be experientially viable. ie, for it to actually work IRL.

Cleary’s/SBD’s focus on inter-connectivity is related to the concept of relativity, of course. According to the theory of relativity, anytime I am experiencing something in spacetime (ie, I am eating a croissant while I wait in line for my coffee), and I would like to explain this experience, there is never a preferable frame for me to reference— ie, if I say that the barista is over there ringing up the next customer while I am over here, chomping, I am, in some respects, misleading my audience. If instead I said, I am over here, in relation to the counter installed in this coffee shop at such and such gps point on the globe of planet earth, my description would be more accurate, but it isn’t possible for me to escape my own perceptive limitations and get, say, the A++ my creative writing students are always working for. (In this scenerio, portrayal of reality is a pesky criterion.)

There is not an easy definition for moving either. Look at the verb in this sentence:

Just be yourself.

“Be” is passive. If you want to take this advice, what do you *do*? How do you move?

Keep in mind that, if you move, you are always moving in relation to someone and/or something. So Cleary’s advice on how to be authentic may be existentialist with all of the term’s nihilistic baggage, but isn’t it also intrinsically humanistic and anti-narcissist? She’s saying: to truly be yourself, you must start from a point of accepting there is no one correct way to “frame” that self— if there was a Movie of You, the movie could never just be from the protagonist’s point of view. That would never work. The movie could never be made.

To start her book from this perspective of uncertainty, and to reiterate that this tension must always be heeded— doesn’t that choice feel somehow, well, less cigarette-threat-y? Leon Garber summarizes this focus nicely:

“Rather than propounding a ‘pick yourself up by the bootstraps’ version of philosophy, de Beauvoir highlights the importance of community and civic engagement for substantial material and psychological change.”

The coolest of the four cool things

Speaking of “the importance of civic engagement for substantial material…”: I know I owe my current understanding of the above ideas to the fact that I did not read about any of them alone. Every week, my questions and theories and summaries and setbacks our reading and guest lectures raised would bounce out in a very meandering fashion, away from myself and into: a multifaceted chorus of alive, (mostly) present, moving flesh sacks, all with their own questions and theories and summaries. The room we were moving in smelled of critical thinking and energy drinks, and never in my teaching career had I lucked into a group of students so collectively curious, truth-seeking, open-minded, fiercely intelligent, and humbly inspired by discoveries in thought and verse.

I’ve been trying to think about how I can reflect on their work: How might I really do my students’ work during that semester justice? How might I share some of their reflections with a wider audience? Because I know that their thinking on the intersection of quantum mechanics and poetry will be important to how I understand the (inter-)discipline— and the discipline’s history— moving forward. And, I really badly want to understand. I am obsessed.

So, contemporary life and pending catastrophes willing, this is the first of a poetry vault miniseries I’d like to call: Thank you, Spring 2025 Particles, For Teaching Me X.

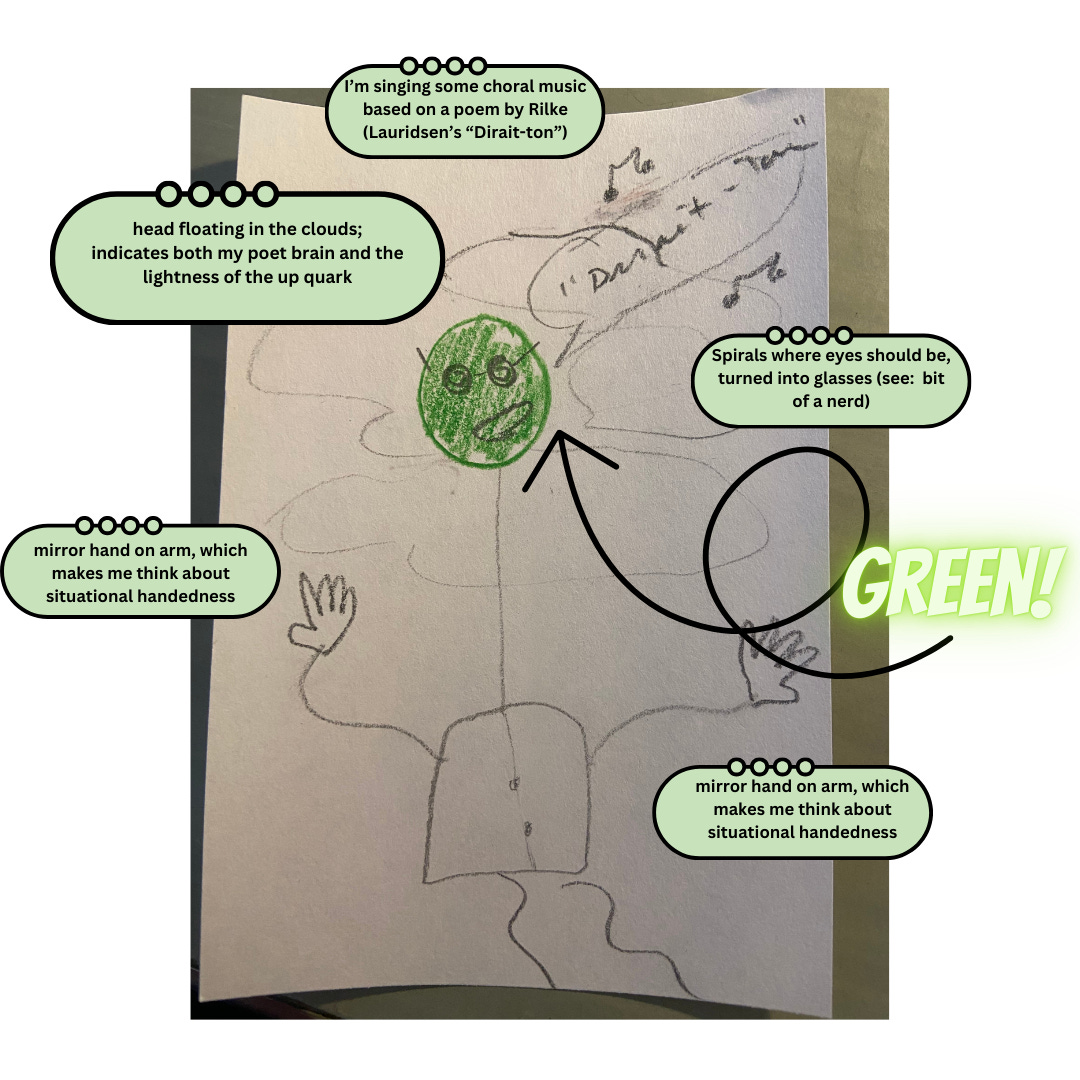

Some brief context. During the class, each student was assigned a quantum particle to learn about throughout the semester, including me.*** We used the particle names in place of roll call names, and we designed self-portraits as (gluon, etc). I got to pick mine, though, whereas they had to forcefully find some similarities between what they saw as their “identity” and an abstract profile of a random subatomic particle. Kudos to the students who received my portrait as a “model” for the first assignment and decided not to drop the class:

I will use these particle identities to share their work ~anonymously with you.

Today, I would like to thank Tetraquark for designing this beauty of a t-shirt to celebrate the end of the semester:

Tetraquark made full use of the t-shirt’s real-life-ness and added some Schrödinger Cat-inspired graphics to both shoulders. On the wearer’s right shoulder, there’s a white cat skeleton; on their left, there’s a profile of a matching black kitty cutout. I can’t but feel like these decisions reflect how particle physicists have organized our understanding of subatomic particles into generations, partly based on the direction of a particle’s spin (or “handedness”).

Tetraquark also used the monochromatic design to emphasize the thought experiment’s over-simplicity. We’d read Benjamin Labatut’s When We Cease to Understand the World, which offered us some maybe true things about Schrödinger, and we learned that the famous cat thought experiment was one that Schrodinger had offered in consternation of— not support for— the Copenhagen Interpretation of the atomic model.**** The experiment was overly simple by design; it was Schrodinger’s way of illustrating what he thought to be a ludicrous theory of quantum jumping. That the tension between Schrodinger and Bohr/Heisenberg’s interpretation of the atomic model was introduced to us via a not-quite-fictional narrative, and in a translation painstakingly crafted by Adrian Nathan West, also speaks to the inevitability of interpersonal exchange. How many steps of representation did we have to go through to get these kitties and non-kitties on our shoulders?

I love the idea of the live cat / dead cat literally hanging out each of my two shoulders. The material-ity of a shirt somehow does push the thought experiment to an extreme, and makes more experiential the abstract, philosophical question at the heart of the quantum jump debate: How do we know what we know? How might what we know about what we know change the very thing we are trying to learn about?

And oh, that delicious t-shirt front, featuring two lines from Bianca Stone’s “The Way Things Were Up Until Now.”

I am going to send 310 Particles an actual t-shirt— if you want one, too, let me know. To those who wear the words of Stone, as you wear the words, I hope you think about the wildness of time in the poem, executed via the relationship of line and syntax. “The Way…” starts from an individual angst, multiple wheelies in the existential hamster cage of trying to live authentically in 2021’s special version of late capitalism. It is short, declarative sentences; it is expected endings that do not break syntactical thought; it is an existentialist struggle up Sisypus’s hill. Still, something surprises our lyrical tour guide— and it’s not the presence of joy, but the oldness of looking for joy that breaks her out of the duldrums.

We’re then directed into a vast ocean of unfolding, complicated syntax, with modifying phrases tumbling in a way that our understanding of the whole is delayed— no, not an ocean, but a field. We are entering into terrain that is metaphorically exactly what it purports to be, in syntax that you can’t untangle without losing a critical referent, a field where nothing can be separate, because it’s all in the same field:

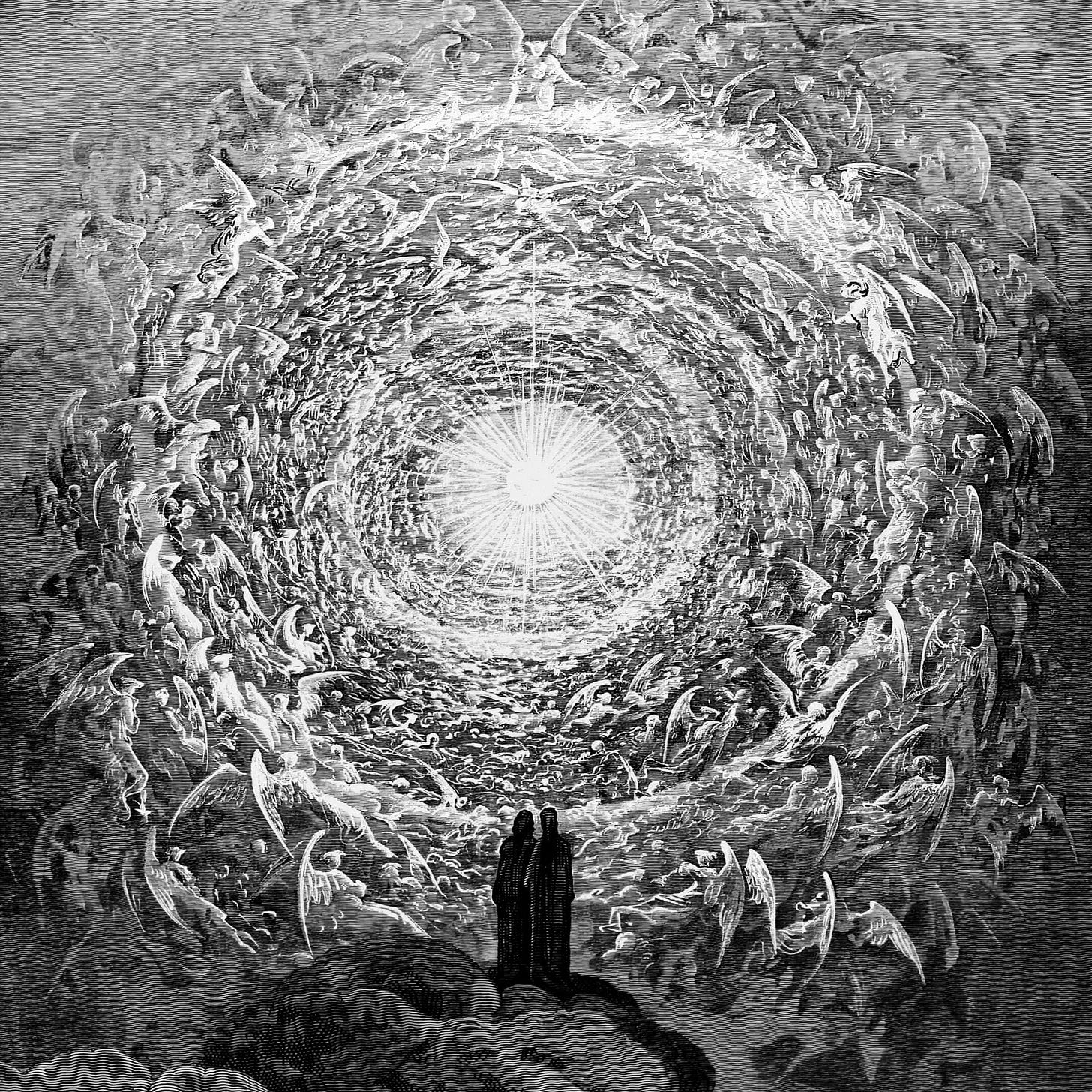

And the world is a field—as if it were indeed flat, curving

and caving, as if it were a piece of paper,

a Gustave Doré engraving

from the Divina Commedia,

the one with the silhouettes of Dante and Beatrice

standing in front of the blinding

exploding white rose

that you realize when looking more closely

is all made up of bodies and wings twisting together;

the “saintly throng,” they call it, mashed and hurtling,

an image of Heaven, and the creation of angels, though it is

frenzied as any image of Hell, around a divine nipple,

Odin’s lost eye in the well, the drain to the other side,

joy that gets more frantic

the more you try to quiet it down.

Let us doggedly***** seek life together, even when that search — or particularly when that search— feels frantic, impossible, unknowable, un-seeable, maybe already gone. And the illusion of separateness?

let it go back into remission.

poetbrain sidenotes:

*Did Cleary dream the name up and then keep it because the dream was so perfect? Or did her parents intuit having a philosophical smarty pants? These are the kind of silly questions I always want to know the answers to.

**facticities = all the things that you think are bringing you down in life, including political systems, family dynamics, environmental factors and catastrophe, genetic predispositions, etc. etc.

***this assignment was inspired by Lynda Barry’s Syllabus

****Physicists please correct me if my over-simplified summary here is badly misleading in someway.

*****Or cattedly, if you’re a cat person?